Code Bonus : « mycasino »

Gamdom

Gamdom Avis

- Résumé :

Gamdom est un site qui propose un système mixte en termes de paiement. Il accepte à la fois les devises fiduciaires ainsi que les cryptomonnaies. Les offres de services de cette plateforme couvrent aussi bien le casino, le casino live, le pari sportif que le sport virtuel. Les amateurs de jeux de casinos ont droit à une vaste ludothèque dans laquelle on retrouve diverses catégories de jeux. Pour profiter de cette large gamme sans compter, Gamdom casino détenu par le groupe Smein Hosting NV offre quelques promotions les unes aussi intéressantes que les autres.

Comme à notre habitude, nous avons investigué sur chaque domaine du casino Gamdom et nous vous proposons dans cet avis un compte-rendu succinct. Certes nous développerons les aspects mentionnés plus haut, mais nous nous intéresserons également au service clientèle, aux conditions de mise associées aux différentes offres de la plateforme. Prêt pour l’aventure ? Démarrons donc.

Gamdom Casino en bref…

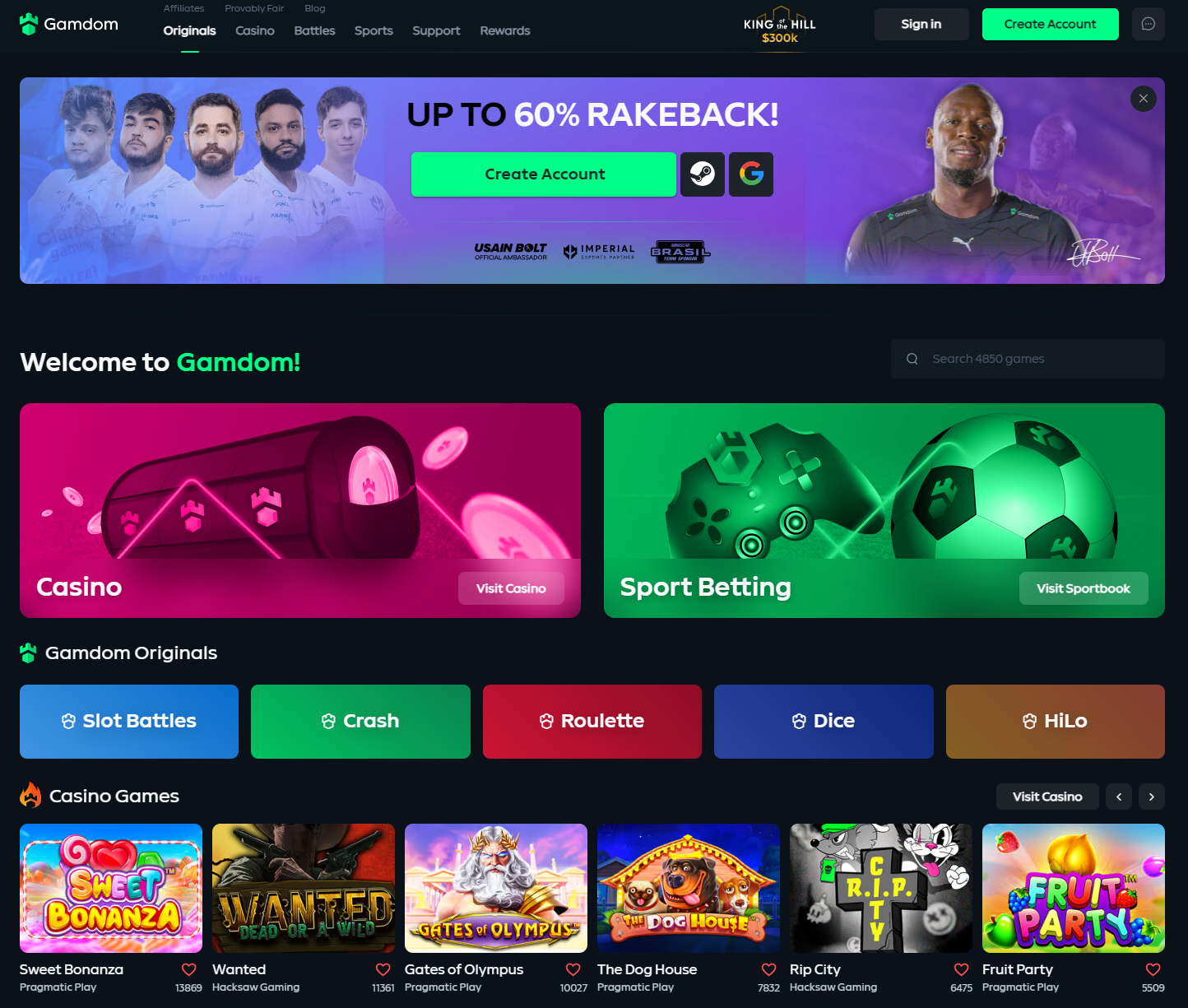

Gamdom présente une interface en fond noir sur laquelle il met en avant les atouts dont il dispose. On y découvre ses promotions, dont un rakeback de 60%. Un peu vers le bas de cette page d’accueil, on retrouve une liste des fournisseurs de logiciel qui alimente le site. Nous avons reconnu la plupart puisqu’ils font partie des meilleurs de la toile. Étant près d’une vingtaine, ils ont fourni près de 4000 jeux de casino avec de nouvelles créations qui sont régulièrement ajoutées. Vous trouverez dans cette gamme de jeux les machines à sous qui drainent le plus de monde sur les casinos en ligne. Sont également présentes les variantes du blackjack, de la roulette ou encore du poker.

Par ailleurs, contrairement à de nombreuses plateformes crypto, Gamdom casino permet aussi à ses membres d’effectuer leurs transactions avec les devises traditionnelles. Ces dernières constituent donc une excellente alternative aux joueurs qui ne s’y connaissent pas aux cryptomonnaies.

Les sections des paris sportifs et des paris sur les sports virtuels sont aussi touffues que celui des jeux de casino. Vous retrouverez une panoplie de sports sur lesquels vous pouvez parier. En somme, il faut dire que le casino Gamdom a priorisé la satisfaction de ses membres dans tous les domaines que couvrent ses services. Et plus bas nous vous donnerons de plus amples détails.

Gamdom Casino : comment s’inscrire ?

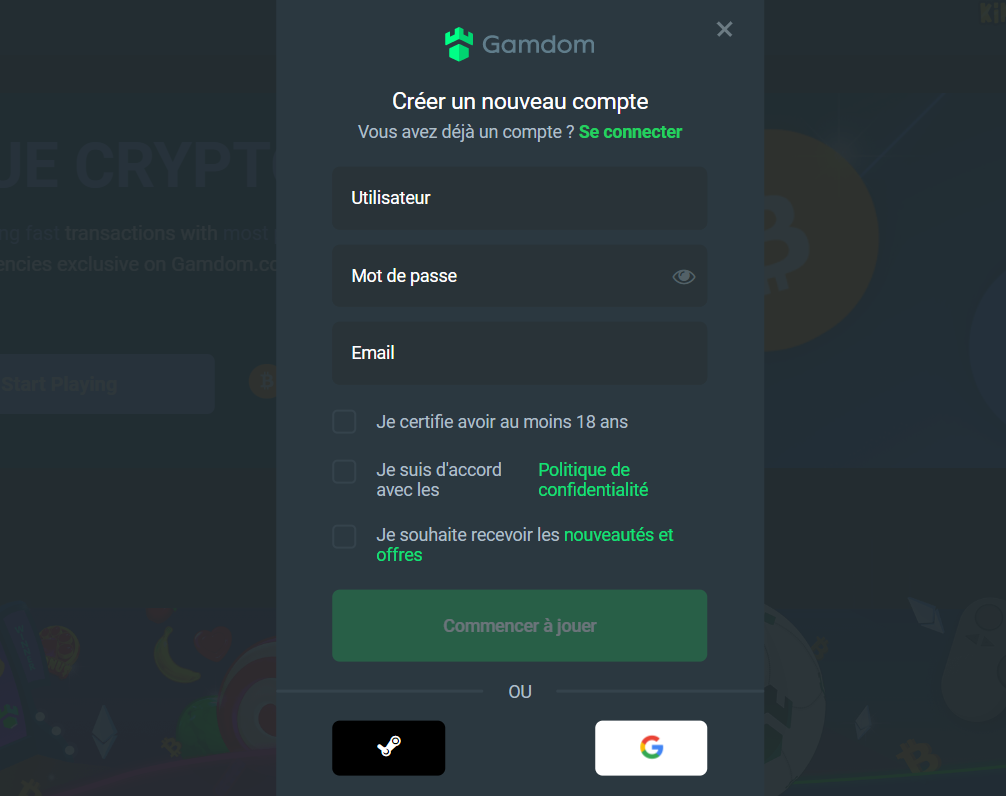

Envie de disposer d’un compte joueur sur le casino Gamdom ? Eh bien, cela se fera en un rien de temps. Cliquez sur « Inscription » directement sur l’interface. Sur la page qui s’affichera, vous devrez créer un nom d’utilisateur, configurer votre mot de passe et ensuite saisir votre e-mail dans le dernier champ.

Mais avant d’aller plus loin, vous devrez cocher une première case pour certifier que vous avez 18 ans au moins, une deuxième pour prouver que vous acceptez la politique de confidentialité du casino Gamdom. Il y a une troisième et dernière case que vous devez cocher si vous désirez être au courant des nouveautés de la plateforme.

Après cette étape, vous n’aurez qu’à valider pour commencer par profiter des jeux du site. Par ailleurs, vous devrez par la suite vérifier votre adresse mail. Même si cela n’est pas nécessaire pour le démarrage, nous vous conseillons de le faire au risque de ne pas pouvoir retirer vos gains.

Gamdom Bonus et Promotions

Après l’inscription sur Gamdom casino, vous pourrez bénéficier d’une panoplie de promotions qui vous permettront de mieux profiter des titres disponibles. Vous aurez droit à un bonus de bienvenue, des free spins, des cashback, et à bien d’autres. Ces suppléments seront associés à de faibles conditions de mise pour accroitre vos chances de retirer vos gains. Il y aura également un club VIP pour un meilleur traitement des membres les plus loyaux.

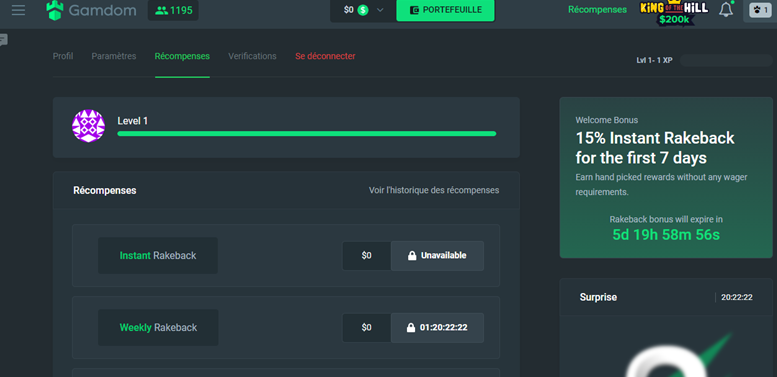

Le Bonus de bienvenue sur Gamdom Casino

Une fois que vous passerez l’étape de l’inscription sur le casino Gamdom, vous recevrez un rakeback de 15% pendant 7 jours. Cette offre est totalement gratuite. Cette implique qu’elle n’est associée à aucune condition de mise. Dès que vous décrocherez des gains à partir de ce bonus, vous pourrez donc lancer le retrait sans aucun souci.

Cependant, pour profiter de cette offre, vous devrez entrer le code bonus MYCASINO. Dès que vous le ferez, le décompte des 7 jours sera lancé. Il est vrai qu’il ne s’agit pas d’un pack avec des correspondances, de free spins, etc. Toutefois, les rakeback proposés vous permettront de démarrer dans les meilleures conditions.

Si vous avez déjà profité du bonus de Gamdom nous vous proposons d’autres casinos en ligne fiables proposant des bonus de bienvenue attractifs comme :

Il s’agit principalement de casinos en ligne acceptant la cryptomonnaie, facilitant ainsi largement les délais de retraits de vos gains et votre anonymat.

Retrouvez une liste complète de casinos en ligne fiables et bonus sur le site de comparaison Mcasinofr.

Gamdom Casino : les autres promotions

Sur la page « Récompenses », vous remarquerez que le casino Gamdom propose 3 types de rakeback. Le premier, c’est le rakeback instantané, le second le rakeback hebdomadaire et le dernier, le rakeback mensuel. Au fur et à mesure que vous jouez, vous profiterez de chacune de ces promotions le moment venu.

Par ailleurs, Gamdom casino vous accordera également des points appelés XP à chaque fois que vous placerez une mise. L’accumulation de ces points vous permettra de débloquer des promotions encore plus intéressantes.

En outre, Gamdom livre une astuce pour bénéficier de 10% de bonus XP gratuitement. Elle consiste à insérer le nom Gamdom.com dans votre nom de profil Steam. Il s’agit de la « Promotion du nom », et vous pouvez déjà configurer le nom dans votre profil après votre l’inscription.

Sur l’interface, vous trouverez également un espace de discussion alimenté par les membres du site. De temps à autre, vous aurez aussi à cliquer sur un robot pour prendre votre part de la cagnotte qu’elle propose : c’est la fonctionnalité Free Rain ou Rainbot.

En dehors de toutes ces promotions, Gamdom casino propose également des offres personnalisées. Dès qu’elles vous seront octroyées, vous pourrez les découvrir dans votre espace « Récompenses ».

Gamdom Club VIP

Le club VIP est l’une des promotions phares du casino Gamdom, même si le site n’a pas fourni assez d’information à ce propos. À travers ce club, cette plateforme attribue un gestionnaire de compte aux membres les plus loyaux. Si vous êtes un amateur des jeux de casino, vous pourrez facilement deviner que le club VIP est bien plus qu’un gestionnaire de compte. Des récompenses énormes s’en suivront sans le moindre doute.

Quels jeux sont proposés par Gamdom ?

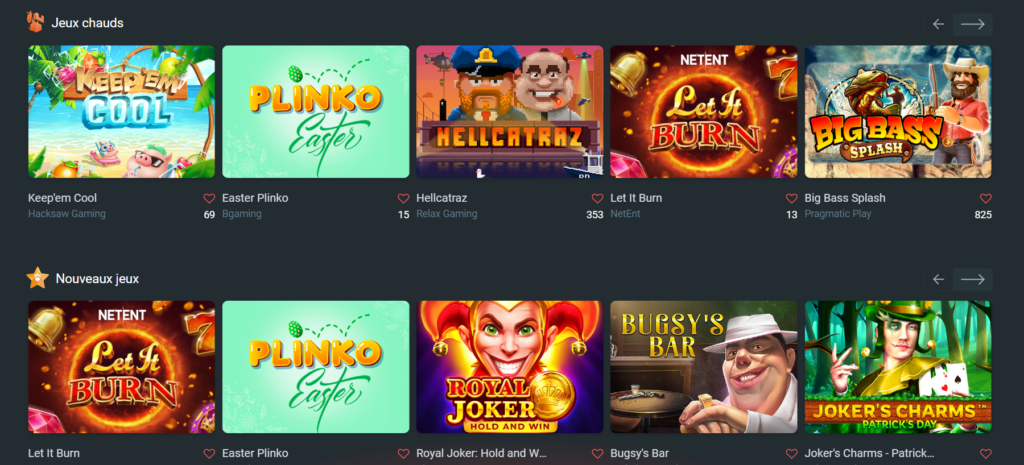

Dans la ludothèque du casino Gamdom, on dénombre près de 4000 titres sur lesquels vous pouvez tenter votre chance. Ces derniers vont des machines à sous aux jeux de table. Les amateurs des jeux avec croupier en direct trouveront également d’excellentes variantes sur lesquelles se divertir.

Les jeux fonctionnant sur la base d’un générateur de nombre aléatoire sont fournis par de grandes marques telles que Betsoft. Cet éditeur qui opère depuis le Royaume-Uni a en effet gravé son nom dans les annales de cette industrie. Il a notamment révolutionné ce secteur avec sa technologie de graphismes et animations 3D qui a été très tôt adoptée par ses homologues.

La sélection To Go constituée des options uniquement accessibles depuis mobile est également l’une des meilleures réalisations de Betsoft. Grâce à cet exploit, les mobinautes ont pu profiter d’un plus grand nombre de jeux au moment où le jeu sur mobile ne courait pas encore les rues. Cet éditeur dispose également d’une sélection de machines à sous progressives avec d’intéressantes cagnottes que les plus chanceux ont pu décrocher.

Mais Betsoft, ce n’est pas que les jeux de machines à sous, sa ludothèque est également composée de variantes de blackjack, de roulette, de poker, et bien d’autres. Et sa particularité est qu’il intègre à ces tables une caractéristique qui les démarque de la version classique et qui met également toute les chances du côté des parieurs.

En raison de ce parcours plutôt élogieux et de cette riche expérience, il est en partenariat avec plusieurs sites de jeux en ligne. Et sur le casino Gamdom, il est associé à d’autres studios de renom à l’instar de Booongo, Red Tiger, Play’n Go, NetEnt, Pragmatic Play, Quickspin, Booming Games, Tom Horn, et bien plus. Quels sont les jeux issus de ces différents partenariats ? Allons-y voir !

Les machines à sous sur Gamdom

Vous êtes un amateur des machines à sous et vous vous perdez peut-être sur l’interface ? Eh bien, il vous suffira de cliquer sur l’icône du menu qui se trouve dans le coin supérieur gauche et représenté par trois traits horizontaux. Ensuite, un clic sur l’option « Machine/Jeux Direct » affichera les jeux de casino. Sur cette première page, vous verrez un classement des jeux selon les éditeurs de la plateforme. Pour uniquement afficher les slots, vous devrez cliquer sur la section correspondante parmi celles affichées en haut.

Cette section contient à elle seule près de 3000 titres dont Rich Wilde And The Tome Of Madness, Razor Shark, Gems Bonanza, Snake Arena, San Quentin X Ways, Release The Kraken, The Hand Of Midas, Hand Of Anubis, etc. Pour ceux qui voudraient profiter d’une expérience nostalgique sur les jeux classiques, Fruit Party 2, Juicy Fruits, Jammin Bars ou encore Extra Juicy combleront leurs attentes.

Pour plus de fun, les opérateurs de Gamdom casino ont annexé à leur plateforme une fonctionnalité spéciale dénommée Slots Battles. Il s’agit en effet d’une sortent de duels auxquels les membres peuvent participer. Ils peuvent créer un battle comme ils peuvent rejoindre un battle qui est sur le point de démarrer. Pour en profiter, vous devez cliquer sur l’option « Slots Battle » dans le menu. Une fois sur la page, vous verrez l’option « Create Battle » qui vous permet de créer votre propre duel. Cette nouvelle façon de profiter des machines à sous permettra aux joueurs de s’en mettre plein les poches.

Il convient de noter que les jeux de machines à sous intègre des caractéristiques qui rendront les sessions plutôt captivantes, et les battles encore plus. Tout d’abord, ils sont développés autour d’intéressantes thématiques telles que les anciennes civilisations, les films à succès, les contes de fées, la science-fiction, et bien d’autres. Pour présenter ces thématiques, les développeurs pour la plupart, utilisent des graphismes et animations 3D, ce qui crée très bien l’illusion du réel.

D’autre part, ces jeux incorporent aussi des fonctionnalités qui rendent l’aventure non seulement divertissante, mais aussi lucrative. Vous retrouverez entre autres un joker, un symbole de dispersion, une partie de free spins et même une partie bonus sur second écran dans certains cas. Et pour couronner le tout, ces créations sont livrées avec un taux de redistribution d’au moins 96%. Mieux, que vous aimiez profiter des jeux à faible, moyenne ou forte volatilité, vous trouverez une machine à sous à laquelle jouer.

Ces jeux sont accessibles en mode démo sans téléchargement et sans inscription. Les joueurs qui désirent découvrir les caractéristiques et le fonctionnement d’une quelconque machine à sous sans prendre de risque peuvent donc jouer sous ce mode. Toutefois, nous rappelons qu’il ne sera pas possible de réclamer les gains que vous remporterez sous ce mode.

Jeux de table

Vous n’aurez qu’à cliquer sur la section éponyme pour accéder aux versions du blackjack, de la roulette, du poker, du baccarat, etc. que propose le casino Gamdom. Dans cette rubrique, vous trouverez des tables populaires comme Dragon Tiger, Casino Hold’em, Rocket Dice, European Roulette, Advanced Roulette, Sic Bo Macau, etc.

Quelques variantes du vidéo poker sont aussi à l’honneur notamment à travers le Joker Poker. Tout comme les machines à sous, les jeux de cette catégorie sont eux aussi disponibles en version instantanée. Pour lancer les jeux sous ce mode, il vous suffit de pointer celui de votre choix et de cliquer sur l’option « Jouer pour s’amuser ».

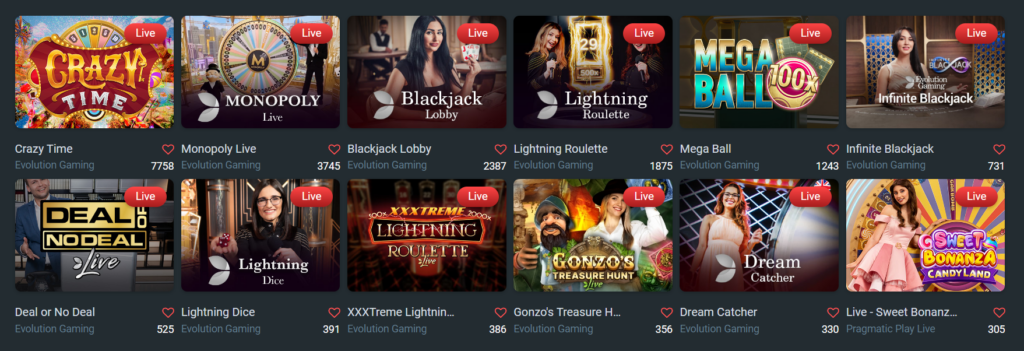

Le casino en direct avec Gamdom

Les tables live gagnent en popularité et chaque jour un peu plus. Ils s’imposent désormais à tous les casinos, du moins ceux qui voudraient accueillir le plus grand nombre de parieurs. Gamdom fait partie de cette catégorie, et si vous êtes un amateur de ces types de jeux, vous pouvez vous attendre à un divertissement à nul autre pareil. Enfouis dans la section « Jeux En Direct », les jeux live sont environ 300.

Ils proviennent des développeurs huppés notamment Evolution, Pragmatic Play Live, Bombay Live. Sur la plupart des casinos live, ces jeux sont classés selon leur nature. Cependant, ce n’est pas ce qui a été proposé sur Gamdom casino. Tous les titres s’affichent directement sur la page. Toutefois, un peu au-dessus, vous verrez que la plateforme offre la possibilité de filtrer par développeur.

Si vous avez un développeur favori, vous pourrez dans ce cas opter le choisir pour ainsi afficher uniquement ses jeux. Par ailleurs, nous précisons que contrairement aux solutions ludiques, les tables live ne sont pas disponibles en mode démo.

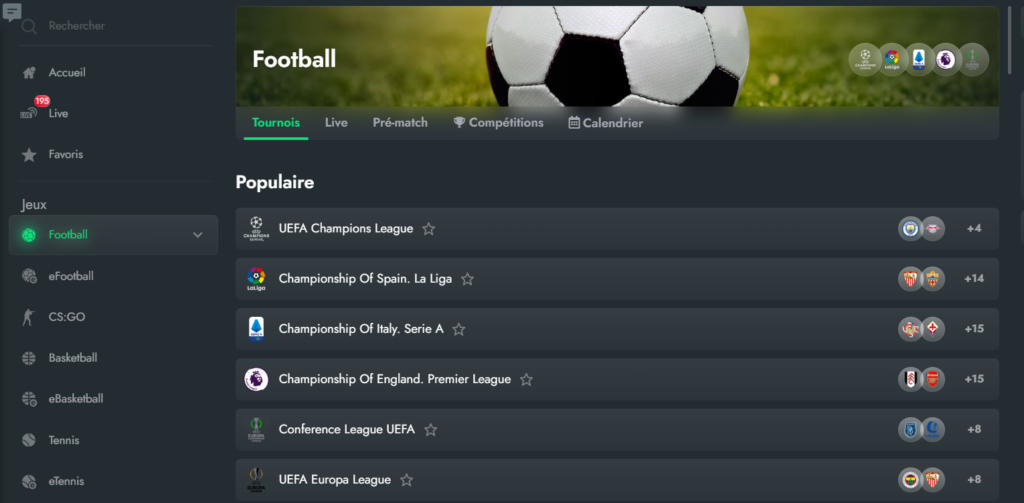

Gamdom Paris Sportifs

Dès que vous accédez à la page de gamdom paris sportifs, vous verrez une option « Live » qui présente les différentes rencontres en cours. Vous pouvez donc saisir l’opportunité et parier sur celle de votre choix. Pour chaque rencontre, vous aurez accès aux statistiques. Elles vous aideront surement à prendre des décisions utiles.

En somme, ce sont près d’une vingtaine de sports qui sont proposés avec des cotes très intéressantes. Nous n’oublierons pas de mentionner la diversité des types de paris que vous pouvez placer. S’agissant de l’Esport, le casino Gamdom vous surprendra sans le moindre doute notamment avec certains jeux esports qui font l’unanimité.

L’offre sportive

Sur le casino Gamdom, vous pouvez parier sur le football, le hockey, le basketball, le tennis, le MMA, le baseball ou encore le volley-ball. Pour chacune de ces disciplines, vous pourrez parier sur une longue liste d’événement : les championnats, les ligues, les tournois les plus importants, vous ne manquerez absolument rien. Pour le football par exemple, vous pourrez choisir de parier sur le championnat anglais, le championnat italien, le championnat portugais, la Liga, et bien plus.

Les types de paris et les cotes sur Gamdom

S’agissant des types de paris, il est à retenir que Gamdom casino ne fait aucune restriction. Il propose un grand nombre de marchés. Vous pouvez par exemple parier sur le vainqueur, le score exact, le nombre de buts, le nombre de carton jaune ou encore de fautes. Le pari handicap est également au rendez-vous.

Les cotes, en format décimal, vous permettront de gagner de modestes sommes. Mais rappelons aussi que ce que vous gagnerez sera en fonction du risque que vous prendrez. En tout cas, pour sa part, Gamdom casino met les moyens à votre disposition pour gagner gros.

L’Esport sur le casino Gamdom

Gamdom propose des jeux virtuels qui cartonnent actuellement sur la toile. Il s’agit notamment de Call Of Duty, League Of Legends, Dota 2, Counter-Strike GO. Il y a également la version virtuelle de plusieurs sports. L’aventure sur les jeux virtuels promet aussi d’être des plus émouvantes.

Gamdom Casino : légalité et sécurité

Gamdom casino a fait légaliser ses services par le gouvernement de Curaçao. Cette juridiction est souvent accusée de légèreté, mais paradoxalement, les sites qu’elle accrédite font partie des meilleurs. Ils proposent des services de qualité, et c’est également le cas du présent site, Gamdom qui opère depuis quelques années déjà sans une plainte majeur à son encontre. En vous inscrivant donc sur ce casino, vous pouvez être sûr de jouer en toute quiétude puisqu’il ne s’agit pas d’une arnaque. En plus d’être légal, Gamdom casino garantit aussi la sécurité des données que vous y laisserez. Le site prend des mesures techniques, administratives et physiques pour protéger quant à la sécurité de vos données.

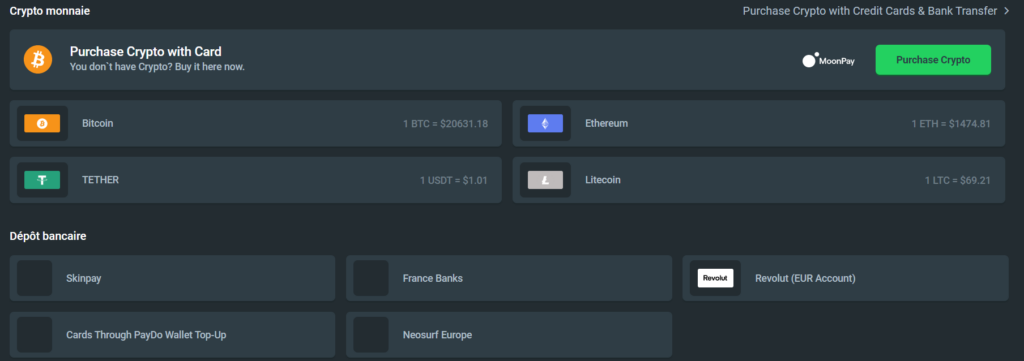

Gamdom Avis sur les moyens de paiement acceptés

Pour les transactions, le casino Gamdom utilise un système mixte : les cryptomonnaies sont acceptées ainsi que les devises traditionnelles. La première catégorie est constituée des cryto devises telles que le Bitcoin, le Litecoin, le Tether, l’Ethereum, etc. Les devises traditionnelles concernent notamment Visa, Mastercard, le virement bancaire, etc. Si les cryptomonnaies ne sont pas votre fort, les cartes bancaires seront donc une parfaite alternative. Parlons à présent des étapes pour effectuer un dépôt ou un retrait.

Comment déposer de l’argent sur Gamdom Casino ?

Vous ferez des dépôts tout au long de votre aventure sur le casino Gamdom, cela est tout à fait évident. Et pour réussir à tous les coups, vous n’aurez qu’à suivre de simples étapes.

- Cliquez sur portefeuille

- Choisissez l’option « Déposer »

- Sélectionnez la méthode de paiement de votre choix

- Spécifiez le montant que vous souhaitez déposer

- Validez la transaction

Comment faire un retrait sur Gamdom Casino ?

Pour effectuer un retrait, le processus est également simplifié.

- Cliquez sur « Portefeuille »

- Ensuite sur « Retrait »

- Choisissez votre méthode de paiement

- Précisez le montant que vous désirez retirer

- Validez la transaction

Comment contacter le service client de Gamdom Casino ?

Plusieurs options s’offrent à vous si vous souhaitez contacter le service clientèle sur le casino Gamdom. La première, c’est la discussion instantanée que vous pouvez lancer en cliquant sur l’icône du casque qui se trouve dans l’angle inférieur droit de l’interface. Vous pouvez aussi leur envoyer votre préoccupation via l’adresse mail support@gamdom.com. Mais avant de faire ce pas, vous pourriez faire un tour dans la section FAQ.

Vous y trouverez des réponses aux questions qui sont fréquemment posées à propos des casinos en ligne. Le site aurait peut-être pris votre préoccupation en compte à travers ses réponses. Mais si vous ne la retrouvez pas, vous pourrez vous adresser au personnel du service client. Il vous réserve un accueil chaleureux.

Gamdom Avis : est-ce un casino recommandable ?

Gamdom casino a démontré à travers ses services qu’il a une parfaite connaissance des attentes des parieurs. il a pris le soin d’étoffer aussi bien la section casino, celle des paris sportifs que celle des sports virtuels. Dans chaque secteur, il propose des offres tout à fait louables. Machines à sous et jeux de tables jeux live se côtoient dans la section casino tandis que les férus des paris sportifs peuvent tirer profit d’une longue liste de rencontre chaque jour. Pour les sports virtuels, Gamdom a carrément sorti le grand jeu avec les jeux virtuels qui actuellement sont très en vogue. De leur côté, les promotions sont disponibles à foison pour ainsi donner un coup de pouce aux membres. Ces nombreux points positifs s’ajoutent au caractère dynamique du service clientèle, à son accréditation, aux différentes mesures sécuritaires, etc. Au vu de tout ce qui précède, on peut donc retenir que Gamdom casino vaut le détour. Les parieurs peuvent s’y divertir en toute quiétude.